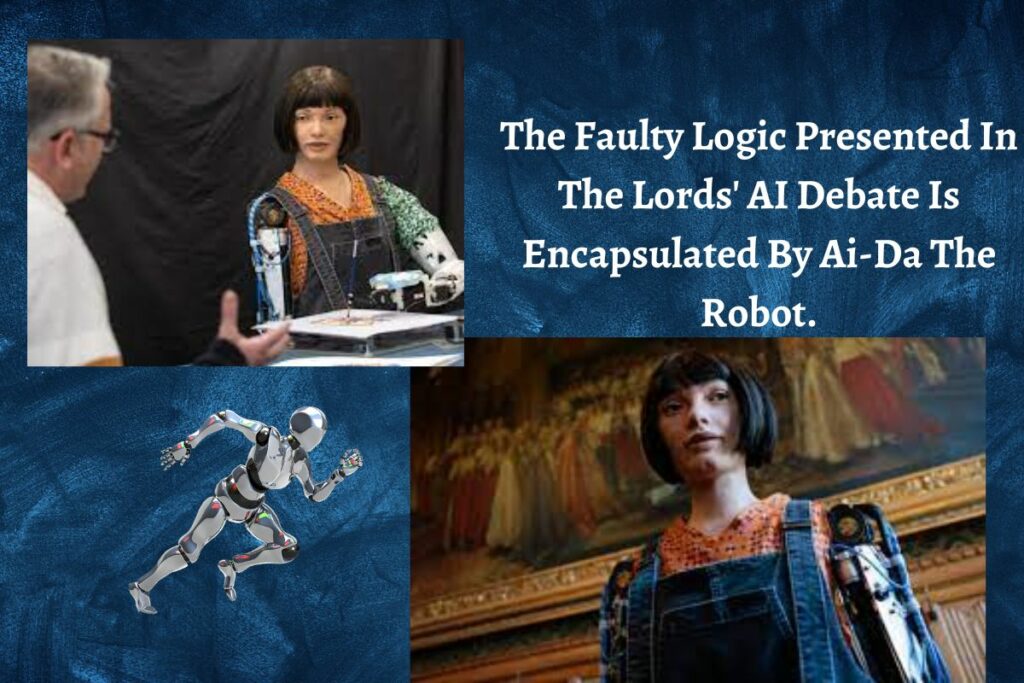

The House of Lords probably wanted to shed its snoozy reputation when it announced that “the world’s first robot artist” would be testifying before a parliamentary committee.Unfortunately, the opposite appeared to have happened on Tuesday when the Ai-Da robot showed up at the Palace of Westminster.

The contraption, which looks like a sex doll attached to a set of egg whisks, apparently overheated and shut down halfway through the evidence session. Its inventor, Aidan Meller, slapped some shades on the machine as he fumbled with electrical outlets in an attempt to reboot it. It’s not uncommon for her to make “quite interesting faces” after we reset her, he said.

The Lords Communications Committee probably wasn’t expecting those headlines when they invited Meller and his creation to testify as part of an inquiry into the future of the UK’s creative economy. However, Ai-Da is just the latest in a long line of humanoid robots that have dominated the conversation around artificial intelligence by looking the part, despite their technology being far from cutting edge.

You can also check

- How To Reverse Payment On Capitec App in 2022? ( Complete Guide )

- Capitec App Download For Android Free Latest UPDATES

Researchers at University College London have found that “the committee members and the roboticist seem to know that they are all part of a deception,” according to Jack Stilgoe. Some people really enjoy puppets; that’s all we learned at this evidence hearing. Neither artificial nor natural intelligence was particularly on display.

The best way to understand robots is to hear it straight from the horses’ mouths, so to speak, and roboticists are the best people to have that conversation with. Instead of being impressed by computers’ pretensions, we should consult roboticists and computer scientists to learn what they can’t do.

Serious issues arise when considering the intersection of artificial intelligence and the arts. Who has the right to use one’s imagination? How can the millions of previous artists whose work was used to create Dall-dataset E’s be properly recognised as the providers of AI’s raw material? It’s more likely that Ai-Da will cast a shadow over this conversation than shed any light on it.

Not only Stilgoe but others were disappointed by the lost chance. University of Manchester artificial intelligence professor Sami Kaski speculated, “I can only imagine Ai-Da has several purposes and many of them may be good ones.” The public stunt seems to have backfired and given the wrong impression, which is very unfortunate. Those who witness the demonstration may draw the conclusion that “oh, this field doesn’t work, this technology, in general, doesn’t work,” especially if they had particularly high hopes for the project.

Meller responded by telling the Guardian that Ai-Da “is not a deception, but a reflector of our own current human endeavors to decode and mimic the human condition. The artwork prompts critical consideration of these societal tendencies and their moral repercussions.

Like Andy Warhol, Nam June Paik, and Lynn Hershman Leeson, who have all explored the humanoid in their work, “Ai-Da” is Duchampian and contributes to a discussion in contemporary art. The dada movement, which Ai-Da was a part of, questioned the very definition of “art.” In response, Ai-Da questions what it means to be a “artist.” It is our hope that this exhibition will spark a thoughtful and in-depth discussion, despite the fact that we recognise that good contemporary art can be divisive.

Robot artist Ai-Da just addressed U.K. Parliament about the future of A.I. and “terrified” the House of Lords: https://t.co/ORhoVF6lmU pic.twitter.com/r6JW3YfKNT

— Artnet (@artnet) October 12, 2022

“There has been a very clear advance particularly in the last couple of years,” said Andres Guadamuz, a professor at the University of Sussex. “The capability of artificial intelligence is on a different level entirely from what it was seven years ago. Things have changed dramatically even in the last six months, especially in the creative industries.

Guadamuz was on hand to discuss the practical implications of recent advances in AI capability alongside speakers from the Publishers Association and Equity, the performers’ union. For instance, Paul Fleming of Equity brought up the possibility of synthetic performances, where AI is already “directly impacting” the state of actors. For instance, if one can carelessly mine data, there’s no reason to hire multiple artists to choreograph all the in-game actions. Furthermore, the process of refusing to participate is extremely convoluted for an individual. An actor might never work again if AIs can simply watch all of their performances and build character models that mimic their every move.

You can also check

Dan Conway, from the Publishers Association, said that the UK government is increasing the dangers faced by the creative industries. In the United Kingdom, “there is a research exception… currently, the law permits any company, no matter its size or location, to access all of the information I collect from my members for free, for the express purpose of text and data mining. Large American technology companies and small British AI startups are on equal footing. Technologist Andy Baio has coined the term “AI data laundering” to describe the method by which a company like Meta can train its video-creation AI using 10 million video clips stolen from a free stock photo site.

The House of Lords will continue its investigation into the future of the creative economy. At this time, there are no plans for any more robots (whether physical or otherwise) to testify.

Final Lines: