A surprise comeback after a close run-off election on Sunday, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva has been chosen as Brazil’s next president. After four years of Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right government, his triumph signals a political about-face for the biggest nation in Latin America.

With his victory, the 76-year-old politician brings the left back into power in Brazil and brings an end to a spectacular political comeback for Lula da Silva. The latter was imprisoned for 580 days following a slew of corruption allegations. His path to running for reelection was opened up when the Supreme Court later overturned the sentences.

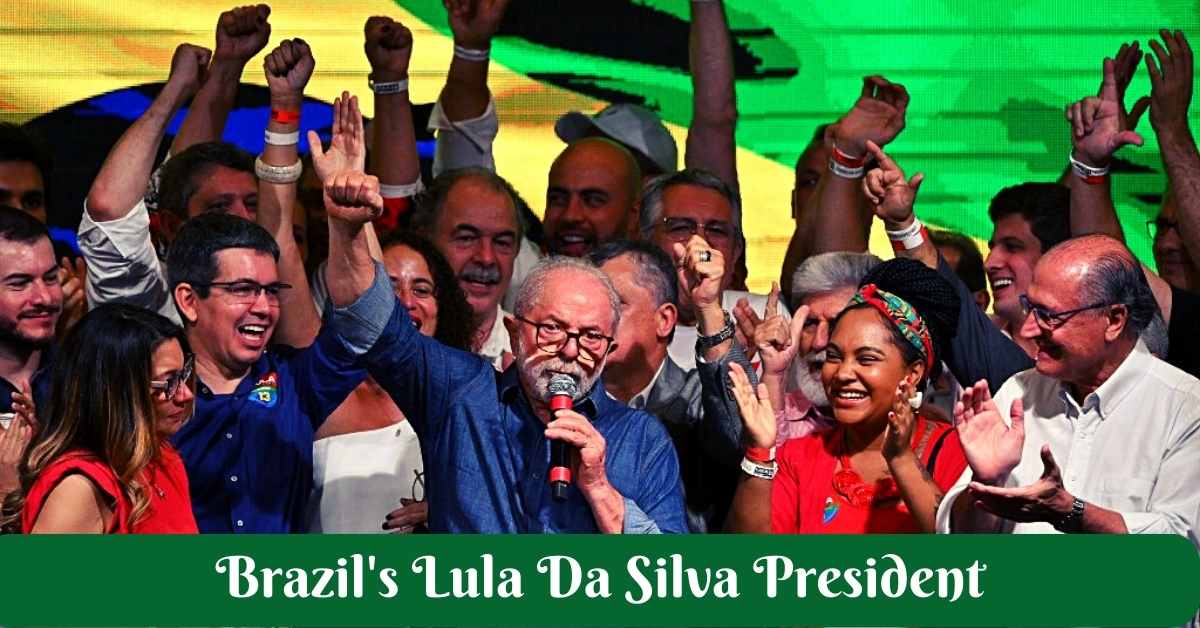

In a triumphant speech to fans and journalists on Sunday night, he declared that the victory was his political “resurrection,” adding, “They attempted to bury me alive, and I’m here.” “I will rule for the 215 million Brazilians, not just the ones who voted for me, starting on January 1, 2023.

There is only one Brazil. Lula da Silva added, “We are one nation—one people, one wonderful nation. He will assume control of a government still working to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic and is racked by extreme inequality. Between 2019 and 2021, 9.6 million individuals lived below the poverty line, while literacy and school attendance rates declined.

He will also have to deal with a severely divided country and pressing environmental problems, such as the widespread destruction of the Amazonian rainforest. After already leading Brazil for two terms in a row between 2003 and 2010, this will be his third tenure.

Also, Check Out

The Most Recent Leftist Surge

The former president’s victory on Sunday was the most recent in a wave of left-leaning candidates winning elections around Latin America. But throughout his campaign, Lula da Silva—a former union leader with a blue-collar background—sought to reassure moderates.

His broad coalition now includes many centers- and centre-right lawmakers, including former rivals from the PSDB, Brazil’s Social Democrat Party. Geraldo Alckmin, a former governor of So Paulo, is one of these politicians and has been mentioned by the Lula camp as a guarantee of moderation in his administration.

When it came to outlining an economic policy during the campaign, Lula da Silva was cautious about showing his hand, which drew harsh criticism from his rivals. Who is the economic minister for the opposing candidate? He doesn’t say that there isn’t one. What political and economic course will he take? Added state? Fewer states? On October 22, Bolsonaro declared during a live YouTube broadcast, “We don’t know…

According to Lula da Silva, he would lobby Congress to pass a tax reform that would exempt those with modest incomes from paying income tax. And the third-place finisher in the first round of voting earlier this month, centrist former presidential contender Simone Tebet, who endorsed Lula da Silva for the second round, provided his campaign with a boost.

In a press conference on October 7, Tebet, who is well-known for her connections to Brazil’s agriculture sector, declared that Lula da Silva and his economic team had “accepted and implemented all the suggestions from our program to his government’s agenda.”

Additionally, he has the backing of many well-known economists who are well-liked by investors, including Arminio Fraga, a former head of the Brazilian Central Bank.

Congratulations to @LulaOficial. #Brazil is now back on the path of peace and unity. https://t.co/10WdejSQ6f

— PES

(@PES_PSE) October 31, 2022

Healing A Divided Country

More votes were cast for Lula da Silva than any other candidate in Brazilian history, beating his record from 2006. Even nevertheless, Bolsonaro’s victory was by a razor-thin margin; according to Brazil’s electoral authorities, Bolsonaro received 49.10% of the vote against Lula da Silva’s 50.90%.

Unifying a politically divided nation may be his most complex challenge at the moment. Bolsonaro still hadn’t announced his defeat or made any public remarks hours after the results were known. Videos posted to social media during this time revealed that his supporters had shut down two state highways in protest of Lula da Silva’s victory.

In a video shot in the southern state of Santa Catarina, one unnamed Bolsonaro supporter shouted, “We won’t leave until the army takes over the country. According to Carlos Melo, a political scientist at Insper University in So Paulo, Lula da Silva will need to pursue discussion and repair relationships.

He said that as long as he is not simply concerned with speaking to his base of supporters, the president may be a valuable tool in this. Lula da Silva will need to form “pragmatic alliances” with elements of the centre and the right that supported his predecessor’s politics, adds Thiago Amparo, professor of law and human rights at FGV business school in So Paulo.

Bolsonaro, who had received more than 58 million votes, had been endorsed by former US President Donald Trump. Amparo continued, “At the same time, he will have to perform to live up to fans’ expectations.” “Many voters went to the polls expecting that, not just because they wanted to get rid of Bolsonaro, but also because they had memories of better economic times under Lula’s prior administrations.”

Many people will keep an eye out for future changes to the 2017 Labor Reform Act, which made union donations optional and subjected additional employee rights and perks to negotiations with employers.

After receiving objections from the commercial sector, Lula da Silva recently reversed his previous promise to “examine” the measure. Amparo cautions that he may find it challenging to carry out his plan, especially in the face of a hostile Congress.

Amparo emphasizes that seats once held by members of the traditional right are now owned by members of the extreme right, who are challenging to work with and unwilling to negotiate. Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party saw gains in the most recent elections, rising from 76 to 99 lower house deputies and 7 to 14 senators.

Although the Workers’ Party of Lula da Silva has added more senators and deputies, the next legislature will still be dominated by legislators with a conservative tilt from seven to eight. Camila Rocha, a political scientist at the Cebrap think tank, notes that this friction will need certain concessions.

Rocha told CNN that “[Lula da Silva’s] Worker’s Party will have to sow a coalition with [traditional rightwing party] Unio Brasil to govern, which means negotiating of ministries and key positions.” Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party will have the most representatives and significant allies and will make real opposition to the government.

The Amazon And Climate Leadership

Meanwhile, environmentalists will keenly monitor Lula da Silva’s administration as it gains control over the Brazilian nation and the most outstanding forest reserves on the planet. Lula da Silva consistently stated throughout his campaign that he would work to stop deforestation, which has reached record levels under Bolsonaro’s leadership.

Brazil election live: Lula triumphs over far-right incumbent Bolsonaro in stunning comeback https://t.co/uvRYX4CBxi

— Tanya Talaga (@TanyaTalaga) October 31, 2022

He has stated that conserving the forest might result in some financial gain, citing the potential benefits of biodiversity for the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries. In an August interview with international media, Lula da Silva urged the creation of “a new world governance” to combat climate change. She emphasized that Brazil should play a vital role in that governance due to its natural riches.

Aloizio Mercadante, the leader of Lula da Silva’s government plan, claims another strategy will be to form a coalition with Brazil, Indonesia, and Congo before the UN-led Conference of Parties in November 2022.

The group would seek to exert pressure on wealthier nations to provide funding for the preservation of forests and to lay out plans for the global carbon market. According to some analysts who spoke with CNN, Brazil’s foreign relations could be restarted by his position on the environment and climate change.

After Bolsonaro warned the world against interfering in the destruction of the Amazon, Amparo believes that environmental protection might serve as a springboard for Brazil’s global leadership.

In the international arena, “Lula would try to recast, almost like a rebranding, Brazil as a power to be taken into account,” he said. The Insper researcher, Melo, stated, “we may expect a government that goes back to talking to the world, especially with a new attitude in the environmental domain.”